Content design is a new-ish field. I say that because it hasn’t really been showing up in job searches until more recently, like pre-pandemic times.

It’s not one of those common jobs that most people have heard of: account manager, marketing coordinator, engineer, developer, and the lot. Most people have a sense of what people in these roles do, or at least know some of their job responsibilities.

But when it comes to content design…not so much. When I tell people this is my job title, the reaction I get is a lot of polite smiles and nods with a glazed look in their eyes.

So I’ve tried to change my approach, and have used some of these descriptive sentences:

- “I work with UI/UX professionals on words in their designs”

- “I am responsible for all of the words in an interface”

- “I’m in user interface and user experience design, and specifically, I help out with the words.”

- “I help the user respond to the system”

- “I write the copy you see on the screens”

And unfortunately, none of these land with the audience. So I’m back to where I started.

Through all of these trials and tribulations, I’ve realized that I can’t just describe what I do. I need to use a story. Stories are universal, and they help set the stage by showing and telling.

So instead I become a storyteller to describe what I do when I sit down at my computer, sip my coffee, and dive into Figma files and Sharepoint sites.

I end up telling the same familiar story

I have one particular story that I tell over and over again. And I use this particular story because it:

- has a low-barrier to entry

- is common and relatable

- ties into people’s emotions

The story goes a little something like this:

Okay, so do you know how you usually log into your favorite app or website? When you open it up, you may get a screen or two that asks you to log in with your user name and password, along with some other brand-specific information.

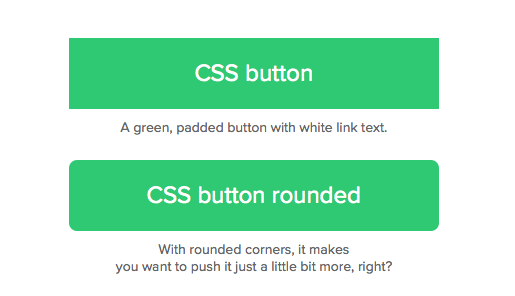

All of the words you see on the screen are my responsibility. I’m the person who helps write the labels for the fields, like “username” and “password.”

But what if you’ve never had an account, so you need to create one? I’m also person who writes the the series of screens to help you create a new account.

Or maybe you’ve been here before, but it takes a little while to get you to your home page with personal preferences? I’m the person who writes the message on the loading screen.

And I’m also that person who helps you when you can’t log in. You try to log in and then you get stopped, and you’re frustrated because you don’t know if its because of your username, password, internet connection, app update, or anything else. I’m the person who writes, “Hey, looks like you’re no longer connected to the internet. Check your connection before logging in again.”

And the words you see as soon as you’re logged in are my responsibility, too.

This story is something everyone can relate to…they’ve been there before. So it helps everyone can better understand what I do on a day to day basis. It also keeps me from getting into the weeds about my work, like discussing ampersands or the use of the Oxford comma (yes, I believe in it and we use it).

Storytelling is what content designers do

It’s interesting that I start with a story, because a lot of what I do as a content designer is revolves around storytelling (how meta). I use stories to talk about points of friction for users. I use stories to talk about collaboration. And I use stories to make connections.

My content design team has a bunch of really good storytellers. We’re able to set the stage, provide the context, and lead everyone on a journey—all while putting our own personal flair on it.

And its not just oral storytelling. Stories come in different formats: PowerPoint slideshows, Miro boards, Figma frames, sticky notes, and more.

As a team, we have been able to do a lot with storytelling:

- We crafted a presentation that allowed us to tell a story about content designers and what happens when you work with them

- We told stories about complex problems we faced during our team working sessions

- We talked about how content designers could get more embedded into teams — how we could do it, and how we could empower our design partners to be more inclusive

- We talked about our success stories with our design partners

- We had a team book club and read “Storytelling for User Experience”

Now you’re probably like, “All of this sounds great, but what does it really mean?”

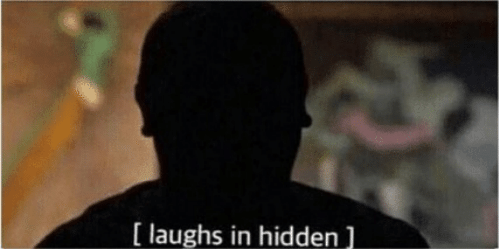

This art of storytelling has allowed us to not only explain our jobs, but also do our jobs. It’s kind of like our hidden superpower. That, and asking questions, but that’s for another post.

So next time you’re stuck on how to tell someone what you do as a content designer, remember to use your superpower. And be thankful it didn’t take a spider bite or a radioactive substance to give it to you.